Sugar by Jeffery Renard Allen

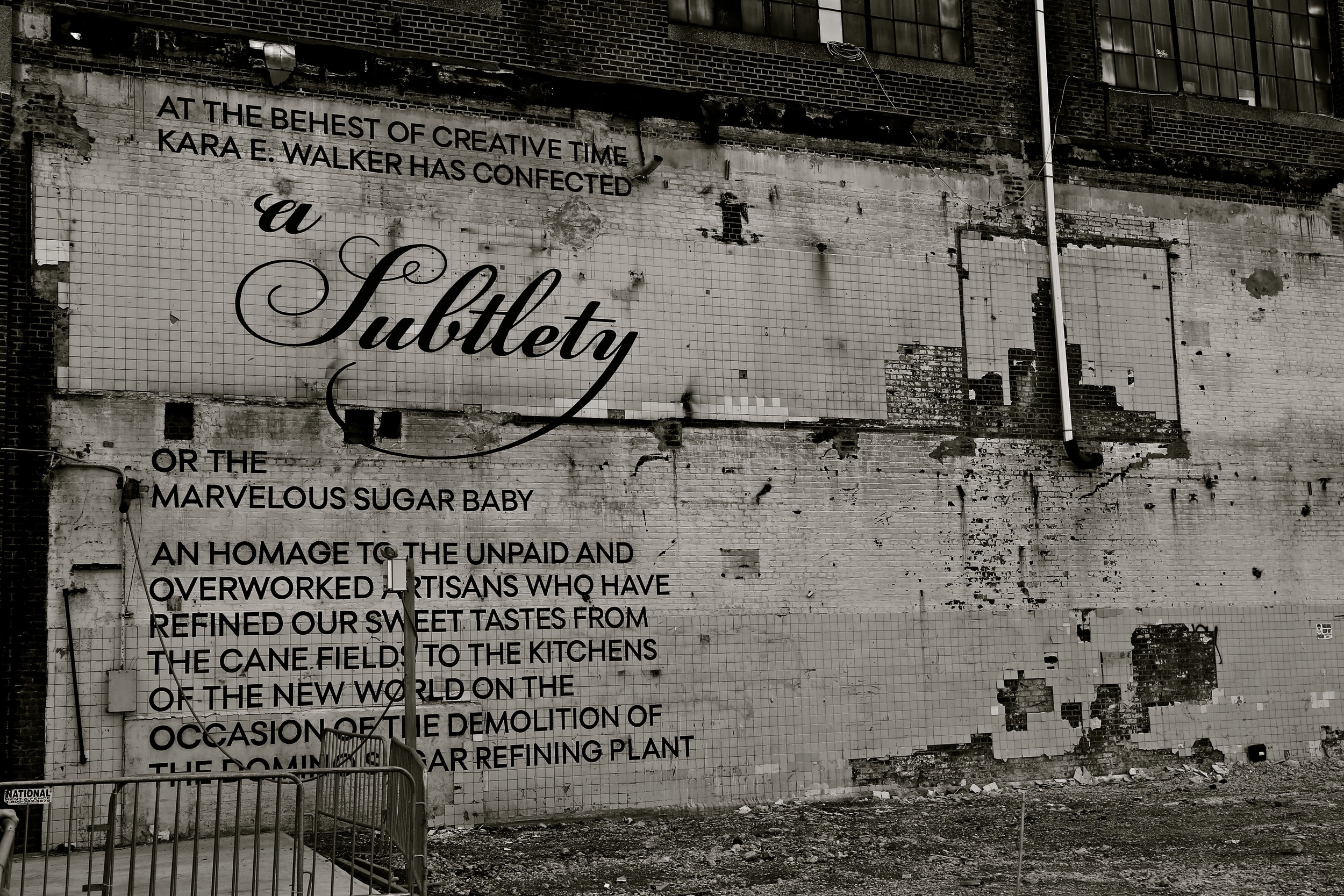

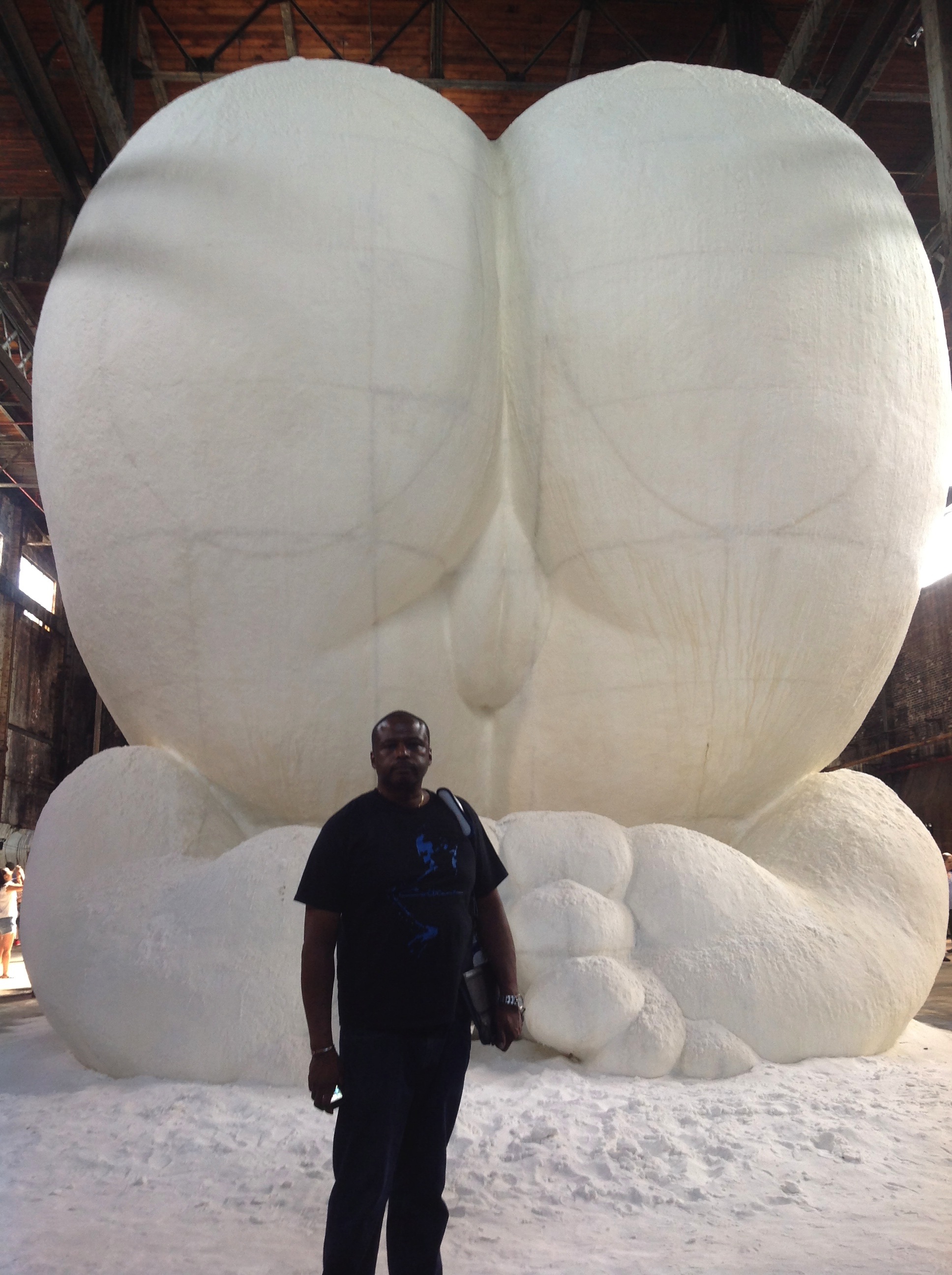

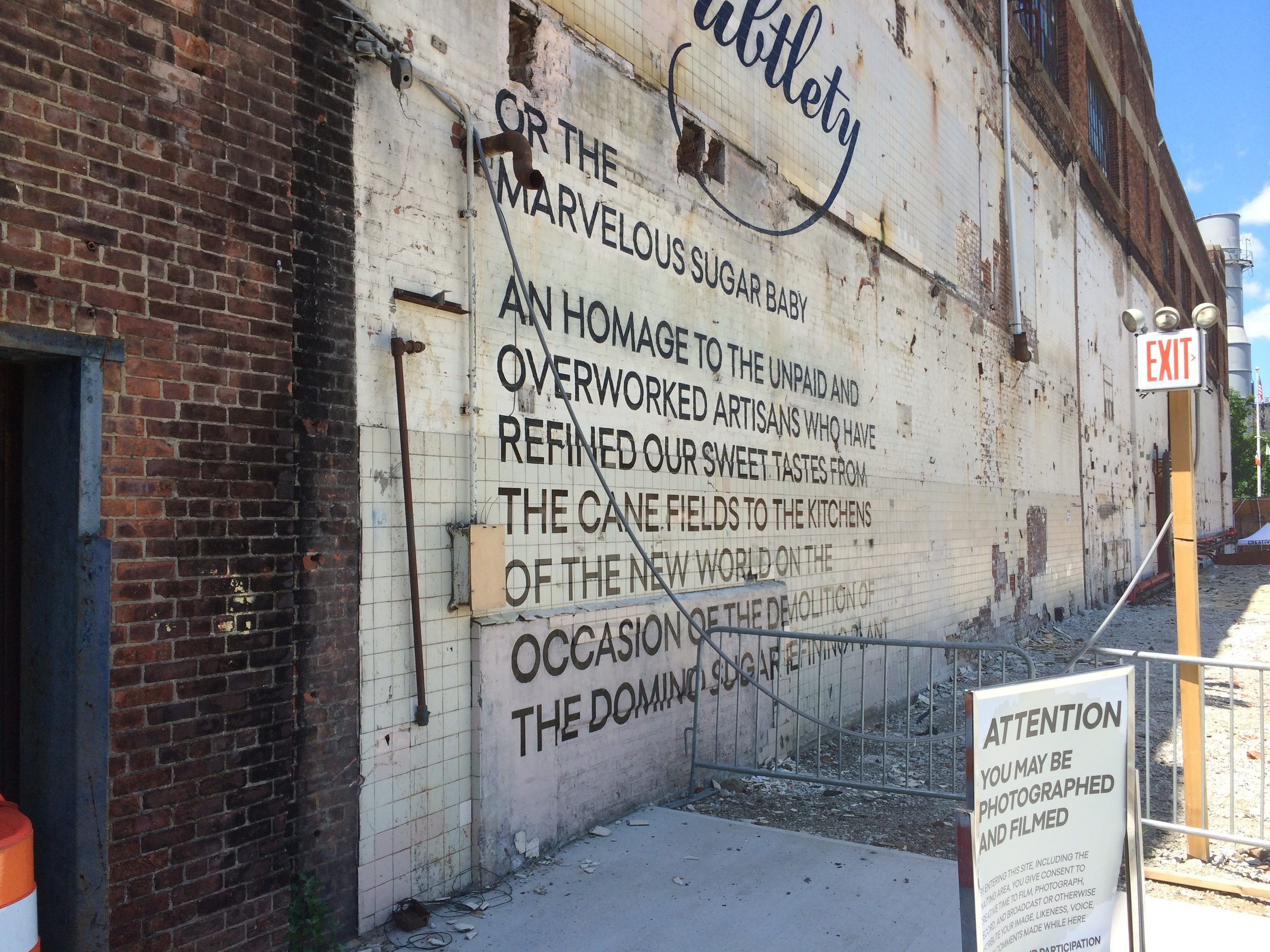

This year on my birthday, I went to check out the Kara Walker installation "A Subtlety" at an old Domino sugar warehouse in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Stood for a good hour or so in a line that stretched for several blocks, seemingly all of New York waiting in line that day since the show would close to the public the following day, our need to visit the space all that more urgent because once the space closed there would be no opportunity in the future to see Walker's ephemeral sculptures, fated as they were to be dismantled and hauled off to a recycling plant, or sold to private collectors, or left simply to rot away--a nod in part to the quickness of change in America--out with the old, in with the new--how an abandoned building can become prime realty seemingly overnight, how a low-rent urban wasteland can become a high-rent neighborhood in the wink of an eye. Indeed, the warehouse will soon be converted into luxury apartments in America's ongoing project of urban gentrification.

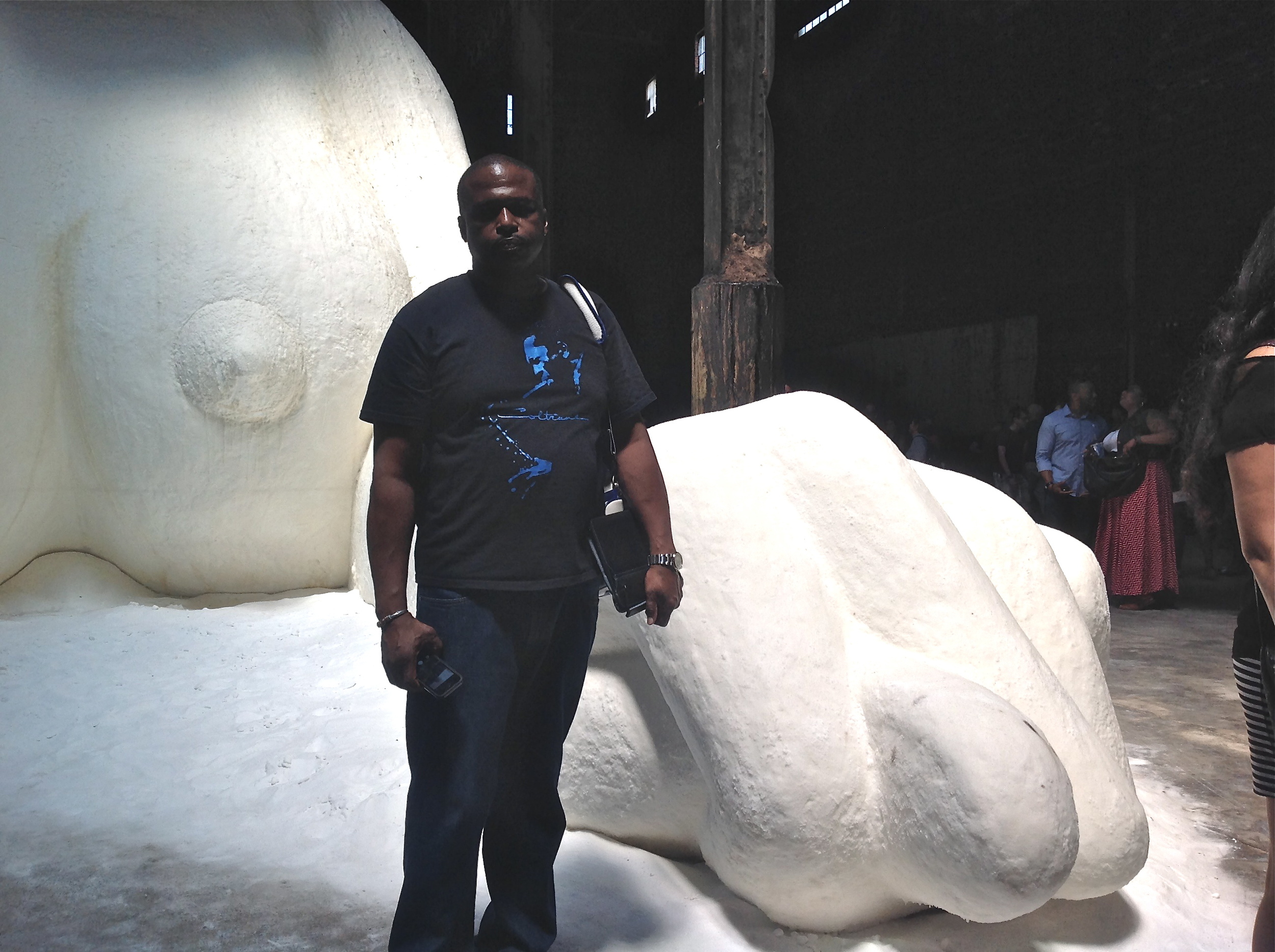

So I weathered the weather and remained in the long line until I was permitted inside the warehouse for a span of time with a group of two or three hundred other visitors. And for that moment until now the installation has given me no end of trouble. I have been brooding over it for the past month, taking myself back, looking again and again at the photographs I shot, reading this and that, checking out one website after another trying to understand it all, trying to put myself in it.

Walker's art has always been about the black body in the popular imagination, about black flesh as the site for projection, illusion, and desire, and for that reason her work can only take on meaning in a rich, broad context of allusion, suggestion, riff, and reference. An aesthetic that forces us to examine anything she creates in relationship to certain other images, notions, assumptions, and narratives that have come before it, that have been around in the American psyche for centuries, namely that vast body of social and cultural material that forms a thick voluminous anthology of stereotype that has become part of the American collective unconscious. In glancing back this way, Walker is of course asking us to look honestly at race and gender dynamics in our country today, no easy thing in this supposedly post-racial equal-opportunity society, in a country that wants therapy and not art, truth.

So let us begin here: where the creators of the Sphinx at Giza outside Cairo (the world's oldest and most famous sphinx) built it to last forever as a "living image" carved out of "living rock," bedrock limestone, Walker from the start conceived of her Sugar Baby as disposable, a beautiful but disturbing object constructed out of blocks of polystyrene foam coated in sugar. And in stark contrast to the nenes scarf that represented kingdom in ancient Egypt, Walker's Sugar Baby wears a servant's doo-rag, like Aunt Jemima of the sweet sticky tasty breakfast syrup, or Hattie McDaniels in Gone with the Wind, and other such stereotypical mammies derived from Plantation literature and minstrel theater. Indeed, Sugar Baby is all woman, and (no surprise) a black woman at that, in direct contrast to Egyptian sphinxes who could be either male or female, a representation of either king or queen with a lion's body and a human head.

It was the ancient Greeks who first conceived of the Sphinx as solely female, as part woman, part beast, and it was also these ancient Mediterraneans who bastardized a word they borrowed from Egypt to give us the word sphinx, which means the "strangler," an apt description since strangulation was the fate of those who failed to answer the fabled riddle. Famously, Freud called the riddle of the sphinx the "question of where babies come from." Indeed, it would seem that Walker's Sugar Baby is mother (mammy) to the life-sized brown children posed in positions of labor about the warehouse with baskets and bowls, their jolly cherubic faces profoundly at odds with their backbreaking work. Indeed, sentimentality is the superstructure erected upon exploitation and brutality: whether cast in plastic coated with sugar or cast completely in candy, each and every child (sugar baby) is in some form of decay. Others have already rotted away into sticky stinky puddles filled with lumps of molasses, long black streams stuck in still-life along the warehouse flood. Nothing sweet about any of this once we acknowledge the history of the millions who slaved away on sugar plantations and inside sugar factories in the New World, once we recognize the many thousands who still slave away in cane fields in the Americas, or think about the many Americans who die yearly from diabetes and other diseases related to excessive sugar consumption. Walker knows the sufferings of a world that is neither beautiful nor good nor sweet, a world that rolls on without hope through the eternally repeated everyday.

But that is not the half of it. For Walker has conjured up the fleshy and bold Sugar Baby, a nude sinfully whole black woman cast in white material that shimmers in the natural light streaming in through windows overhead and on either side. A voluptuous figure with full breasts, fleshy thighs, and wide hips, her butt raised high in her sphinx-kneel, her vagina open and inviting (doggy style), and her feet curved so that the toes on both feet touch in a highly sexualized manner, this doo-rag mammy ready to serve and be serviced. No visible signs of the woman-animal hybridity that we have come to expect from Greek tradition, for the point is to see the black woman through the lens of our assumptions and expectations, our bigotry, longings, and lusts. Whereas her brown sugar babies remain as natural (raw) as molasses, the Sugar Baby has undergone a thorough process of pornographic whitening. (Gal, you sure is sweet. Can I get some of that sugar? Put some of that sugar in my bowl. Brown Sugar, how come you dance so good? Just like a black girl should. I want some of your brown sugar.)

One thinks here of the depiction of black women in Jean Toomer's highly celebrated and influential book Cane (1923), the greatest single work of fiction of the Harlem Renaissance and the the book that Alice Walker called the first womanist (black feminist) novel. But then Kara Walker's work--silhouettes, gouaches, sketches and drawings, murals, photographs, magic lantern projections, animation, videos, and installations--has always been highly literary in the way that it references, reads, and riffs on certain written texts to rework and extend their meaning. (So, for example, in calling one of her exhibitions Dustjackets for the Niggerati, Walker combines Hurston's term " Niggerati " and the title of Hurston's autobiography, Dust Tracks on the Road, to form a suggestive third idea.) "A Subtlety" also brings to mind a famous essay by Immanuel Kant called "The Beautiful and the Sublime" where Kant posits a distinct cultural, psychological, and intellectual difference between men and women. Women are beautiful, while men are sublime. Therefore, the function of the male is to implant the sublime in the female. Walker clearly flies in the face of Kant’s idea in her ability to awaken the sublime in all of us, for as Joseph Campbell said, "Beauty awakes; the sublime shatters."

In counterdistinction to those narrow-minded few who believe that the pictorial elements of Walker's work are intended to be representational, realistic, her art is subliminal, comes from inside, strives to depict inner landscapes, represent certain elements of the American imagination. Of course, who we are inside is largely a construction of our shared past that cast the psychological die hundreds of years ago during the violent birth of this country. Small surprise then that Walker's archetypal images of that past--lynching, rape, flogging, plantations, bondage, domestic service, child labor, etc.--appear time and again in her work in ways that are both grotesquely realistic and profoundly mythic. So all that is strident, abrasive, crude, and offensive in an exhibition like "A Subtlety" is a positive virtue for which it deserves praise since the aim of this method of self-expression is to bring our notions about gender, race, labor, commerce, and consumption into the full light of day and in so doing foster conversation, dialogue, about these subjects.

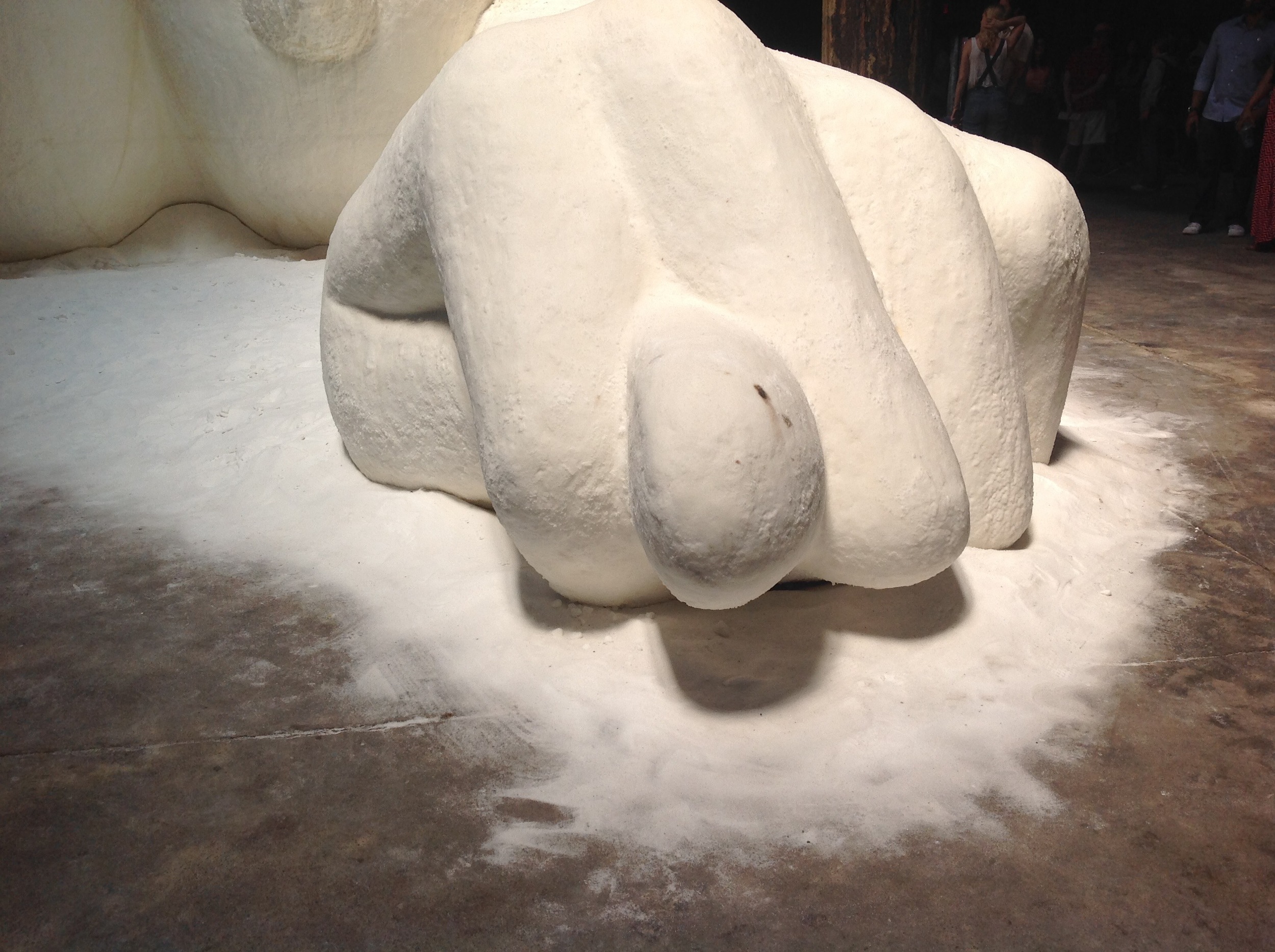

"A Subtlety" also poses some uncomfortable questions about the function and value of art in our society today. Oscar Wilde said that a work of art is something entirely useless. To take this idea further, a work of art should indeed be more than a utilitarian tool, or a product to sale, or a private possession to hang on a wall, or a financial investment to keep behind lock and key. A disposable object from conception, only the left hand of Walker's Sugar Mamma's will be preserved, apparently for Walker's own personal collection, a souvenir, her own good luck charm. Indeed, the fingers of this hand form the gesture of Figa, a popular symbol of a both good luck and fertility throughout Bahia, the center of Afro-Brazilian culture. It would seem that Walker recognizes, acknowledges that none of us have clean hearts and hands, that we are all caught (stuck) in this system of the buying and selling of products and people, that every one of us is part and parcel of a culture of artifice, fabrication, objectification, and fetishization, of greed and lust. Of course, we know that when all is said and done, artists, galleries, and museums profit directly and the most from art. (Fifteen of the sugar babies will be sold to public institutions at a cost of between $100,000 and $200,000 each.) But in what ways do we the public also benefit from art as both individuals and a collective? What is of decisive importance is that we think about Walker's installation in relation to our own daily lives, look closely at how we navigate through the chaged and conflicted waters of labor, sex, and race on a daily basis. So we must ask on the one hand, in what ways are we sugar babies at the service of another? And on the other, in what ways do we treat certain people as disposable objects for our own profit and pleasure?

The twenty writers in this August 2014 issue of Kweli Journal each share in one individualized way or another Walker's aesthetic and cultural dispositions and social and political concerns. Taking my role seriously as a guest editor, I have done the responsible thing and set high standards (the first requirement of good art) and used this occasion to pull together and bring into one space original manuscripts from a wide assortment of writers who are at various stages of their careers, from those who are well-established to those who are seeing their work in print for the first time. As good writing, the stories, poems, and essays here reflect the tensions and uncertainties that we all face as humans. And since the best art cuts several ways at once to reveal the widest range of experience and meaning, these pieces stack the temporal deck, using a single moment to look firmly at the present moment, glance back to the past, and also gaze ahead into the future.

In closing, it is of the utmost importance to note that we dedicate this issue to Kofi Awoonor. Kofi, through a brutal deed they took your physical body away. We bring you back again.

Jeffery Renard Allen

August 7, 2014

Bronx, New York

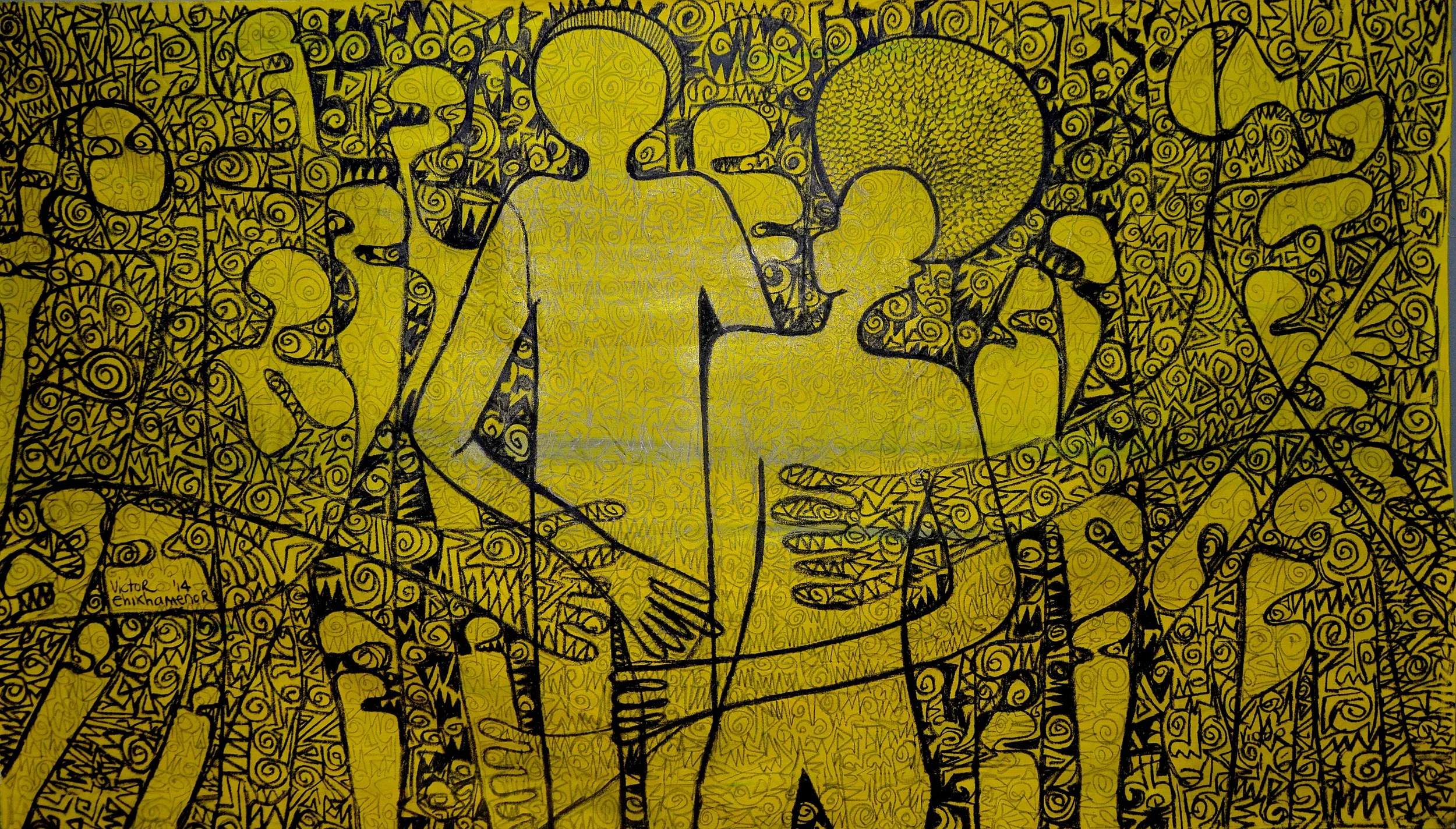

Cover art: Victor Ehikhamenor

Photo credit: Jeffery Renard Allen

CONTENT

Poetry

Boys at the Intersection by Nathalie Handal

Strange Things by Duriel E. Harris

Aubade for West African History by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

Fragrance of a Crush by Kitso Kgaboesele

Writing Reconciliation by Ammon Medina

Moody Indigo by David Mills

After Hurricane Sandy by Cynthia Dewi Oka

The Pocket by Amir Rabiyah

Ritual by Amir Rabiyah

Ghost Voices, Sections 3 to 7 by Quincy Troupe

Prose

At the Buka by A. Igoni Barrett

A Different Breed by Nana-Ama Danquah

Passport to Heaven by Victor Ehikhamenor

Leaving Edina by Kim Coleman Foote

Bumpers by A. Naomi Jackson

Occupying Arthur Whitfield by Charles Johnson

The Blanket by Dwayne Martine

In at the Door Book Three : Inflation by Ed Pavlić

Who Can Afford to Improvise? Black Music and James Baldwin’s Political Aesthetic by Ed Pavlić

Selected Shorts by Dianca London Potts

Sererie by Mecca Jamilah Sullivan

Sensory Deprivation by Chang Yao

Jahannam: A Justification of the Ways of God to Men by Najah Yasin

Interviews

Black, Along the Lines of Mozart: A. Naomi Jackson Interviews Jeffery Renard Allen

Transcendence, A Naomi Jackson Interviews Morowa Yejidé

Knowing Your Own: Jeffery Renard Allen Interviews Edward P. Jones

This guest edited issue was made possible with funding from the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA).